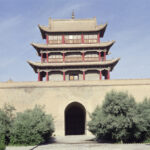

Lahore Fort

The old city sits in the shadow of Lahore Fort, a massive structure that had guarded this centre of commerce for the best part of a millennium. The fortified walls of Lahore Fort speak of centuries of turbulent times. The fort pre-dated the coming of Mahmud of Ghazni in the eleventh century, was ruined by the Mongols in 1241, rebuilt in 1267, destroyed again by Timurlane in 1398 and rebuilt once more in 1421.

The great Mughal emperor Akbar replaced its mud walls with solid brick masonry in 1566 and extended it northwards. Later Jehangir, Shah Jehan and Aurangzeb added the stamps of their widely differing personalities to its fortification, gateways and palaces.

Shah Jehan built the Elephant Gate and opens onto the Hathi Paer, or Elephant Path, a stairway with fifty-eight steps that allowed access by royalty mounted on elephants to the forecourt of the Shish Mahal, the Palace of Mirrors, which lay within the fort. Climbing these broad, shallow steps gave me a brief glimpse into the power of the Mughal Empire. The sight of heavily decorated elephants carrying the power into the inner sanctum of the fort and away from the bustle of the narrow, crowded streets must have been stupendous.

The fort encloses an area of approximately thirty acres and the buildings within its walls stand as a testament to the gracious style of Mughal rule at its height, in which every man knew his place and where courtly behaviour had been refined into an elaborately stratified social code. Much of the architecture reflects this code.

From a raised balcony in the Diwan-e-Aam, or Hall of Public Audience, built by Shah Jehan in 1631, the emperors looked down on the common people over whom they ruled when they came to present petitions and to request the settlement of disputes. Wealthier citizens and the nobility could meet their emperors on a level floor in the Diwan-e-Khas, the Hall of Special Audience, which was also built by Shah Jehan, in 1633.

While the Hall of Audience was characterised by its strict functionality, other buildings raised under Shah Jehan’s patronage were styled in a more imaginative and fanciful manner. Of these the Shish Mahal, which stands on the fort’s north side, was by far the most splendid. It consists of a row of high domed rooms, the roofs of which are decorated with hundreds of thousands of tiny mirrors in traditional Punjabi “Shishgari” style.

As I peered through an ornate archway in the Shish Mahal, the voice of a tour guide echoed across the plaza.

“A candle lit inside any part of the Palace of Mirrors throws back a million reflections that seem like a galaxy of far-off stars turning in an ink-blue firmament.”

The fort is no longer a haven for the wealthy and is instead a meeting place for the people of Lahore and a museum to a way of life that is no more.

Leave a comment